Sour Cherry Pilaf

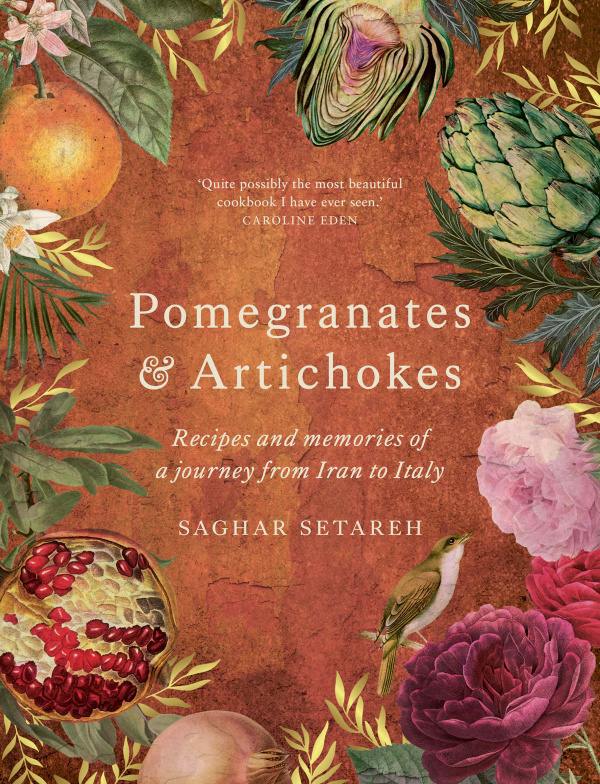

by Saghar Setareh, featured in Pomegranates & Artichokes Published by Murdoch BooksIntroduction

While most children feast on candies and other sweets as snacks, in Iran, what drives kids crazy with an almost manic delight is the sourest treat you can find. Think very tart fruit leathers made mostly of plums, but also barberries, pomegranates or tamarind. Or dried and salted sour cherries, crisp and sour greengage plums in spring (sometimes sprinkled with salt), qareh qurut or black kashk, a by-product of yoghurt (usually a hard paste with the most exquisitely sour flavour you can imagine). At the very north of Tehran, where the capital merges into the foothills of Mount Damavand, there are country-style restaurants and many snack stalls selling all these treats and more, some going the extra mile in feeding this hysterical appreciation for sourness by actually adding acid citric and food colourings, giving a slightly psychedelic look to the bright fuchsia mounds of prunes and many assorted folded fruit leathers. In Iran we’re trained to love sourness, and a sour condiment is almost ever-present in recipes, be it lemon juice, Seville orange juice, verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes), vinegar, or the molasses of sour fruits such as pomegranates or plums.

In A Safavid Period Cookbook, Nour-allah, the chef of Shah Abbas the Great (1571–1629), dedicates an entire chapter to sour polows, in which he describes different pilaf recipes using lemons, quinces, Seville oranges, sumac berries, pomegranates, vinegar, unripe grapes, black mulberries, cornelian cherries, tamarind, barberries and sour cherries as the main flavour, enhanced with many other ingredients. Barberries and sour cherries are the stars of two favourite Iranian dishes to this day: zereshk polow — pilaf with barberries, often served with saffron chicken, and albaloo polow — pilaf with sour cherries, often served with chicken kebabs or tiny meatballs. While the first is very common, the latter is a bit less so, due to the seasonality of sour cherries. This delicate balance between sweet and sour can be found also in the cuisine of Aleppo, in Syria. When eating the Iranian sour cherry pilaf with meatballs, ever so lightly sprinkled with pistachios, you can’t help being reminded of kebab karaz — Aleppian meatballs stewed with sour cherries and topped with toasted pine nuts.

While most children feast on candies and other sweets as snacks, in Iran, what drives kids crazy with an almost manic delight is the sourest treat you can find. Think very tart fruit leathers made mostly of plums, but also barberries, pomegranates or tamarind. Or dried and salted sour cherries, crisp and sour greengage plums in spring (sometimes sprinkled with salt), qareh qurut or black kashk, a by-product of yoghurt (usually a hard paste with the most exquisitely sour flavour you can imagine). At the very north of Tehran, where the capital merges into the foothills of Mount Damavand, there are country-style restaurants and many snack stalls selling all these treats and more, some going the extra mile in feeding this hysterical appreciation for sourness by actually adding acid citric and food colourings, giving a slightly psychedelic look to the bright fuchsia mounds of prunes and many assorted folded fruit leathers. In Iran we’re trained to love sourness, and a sour condiment is almost ever-present in recipes, be it lemon juice, Seville orange juice, verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes), vinegar, or the molasses of sour fruits such as pomegranates or plums.

In A Safavid Period Cookbook, Nour-allah, the chef of Shah Abbas the Great (1571–1629), dedicates an entire chapter to sour polows, in which he describes different pilaf recipes using lemons, quinces, Seville oranges, sumac berries, pomegranates, vinegar, unripe grapes, black mulberries, cornelian cherries, tamarind, barberries and sour cherries as the main flavour, enhanced with many other ingredients. Barberries and sour cherries are the stars of two favourite Iranian dishes to this day: zereshk polow — pilaf with barberries, often served with saffron chicken, and albaloo polow — pilaf with sour cherries, often served with chicken kebabs or tiny meatballs. While the first is very common, the latter is a bit less so, due to the seasonality of sour cherries. This delicate balance between sweet and sour can be found also in the cuisine of Aleppo, in Syria. When eating the Iranian sour cherry pilaf with meatballs, ever so lightly sprinkled with pistachios, you can’t help being reminded of kebab karaz — Aleppian meatballs stewed with sour cherries and topped with toasted pine nuts.

Share or save this

Ingredients

Serves: 4-6

FOR THE RICE

- 350 grams Iranian or basmati-style long grain rice

- 70 grams coarse salt

- 1½ teaspoons vegetable oil

- 1 tablespoon ghee (or half butter, half oil)

- 1½ teaspoons butter

- 1 tablespoon saffron infusion (see below)

FOR THE SOUR CHERRIES

- 500 grams pitted sour cherries either fresh or frozen (see Additional Info below), or 350 g (12 oz) dried, pitted sour cherries

- 100 - 150 grams sugar

SAFFRON INFUSION

- ½ teaspoon saffron threads, very loosely packed

- a good pinch of sugar

FOR THE RICE

- 1¾ cups Iranian or basmati-style long grain rice

- 2½ ounces coarse salt

- 1½ teaspoons vegetable oil

- 1 tablespoon ghee (or half butter, half oil)

- 1½ teaspoons butter

- 1 tablespoon saffron infusion (see below)

FOR THE SOUR CHERRIES

- 1 lb 2 ounces pitted sour cherries either fresh or frozen (see Additional Info below), or 350 g (12 oz) dried, pitted sour cherries

- 3½ - 5½ ounces sugar

SAFFRON INFUSION

- ½ teaspoon saffron threads, very loosely packed

- a good pinch of sugar

Method

Sour Cherry Pilaf is a guest recipe by Saghar Setareh so we are not able to answer questions regarding this recipe

- At least 2-3 hours before you want to serve the dish, gently rinse the rice with cold water, discarding the water. Do this at least three times. The water will always remain a bit cloudy, but rinsing removes the excess starch from the rice, which will make the rice fluffy once cooked, with each grain separated.

- Add the rice to a large bowl, with enough water to cover the rice by at least 5cm (2 inches). Add the salt and fold gently, possibly with your hand. Taste the water: it should be as salty as the sea. Don't worry if the water seems too salty - the rice absorbs the salt it needs, and any excess salt can be rinsed away after the first cooking (the parboiling stage).

- Soak the rice for 2–3 hours, or at least 30 minutes. You can even soak the rice overnight.

- Meanwhile, if you’re using frozen or fresh cherries, let them macerate with the sugar for at least 30 minutes. If using dried cherries, soak them in 1 cup (250 ml) hot water until rehydrated.

- Put the cherries in a saucepan, either with the released juices if using fresh or frozen ones, or with the sugar to taste if using dried cherries. (This is a sweet and savoury dish, so some sugar is needed.) Cook with a lid on for 8–15 minutes, until the cherries are soft, but nowhere near falling apart. Remove them from the syrup.

- Keep about ½ cup (125 ml) of the juices for the rice, and store the remaining syrup to make sharbat.

- Now parboil the rice. Bring a large pot of water to the boil. Add the vegetable oil. Discard most of the soaking water from the rice, without draining it completely, then gently add the rice and what's left of the soaking water to the boiling water. Do not stir the rice too much, or you'll break the grains. If needed, put the lid on to bring the water back up to the boil as quickly as possible. We want to partially cook the rice at this point; meaning the grains will swell, and the outer part of the grain should be soft, but a bit of a bite should remain in the centre (similar to very al dente, if we were talking about pasta). The parboiling time varies depending on the quality of the rice, and even the humidity of the region in which you live. This amount of rice would normally take 5-10 minutes to cook.

- Place a fine-meshed colander in your kitchen sink, then very gently and carefully drain the rice into the colander. Taste the rice. If it's too salty (it shouldn't be), run cold water over the rice for several minutes. Otherwise, run the cold tap water for only about 30 seconds, just to stop the cooking process.

- Melt the ghee with ½ cup (125 ml) water in a heavy-based nonstick saucepan over medium–high heat. With the pot still on the heat, gently scatter in a layer of rice with a slotted spoon, then add a layer of sour cherries. Repeat this layering (never pushing down on the rice), to create a little mountain of rice and sour cherries. Now, using the other end of the slotted spoon, dig some holes in the mound of rice and sour cherries to let the steam rise from the bottom to the top.

- In a small saucepan, heat the reserved cherry syrup with the butter, then drizzle it all over the mound of rice. Wrap the lid in a clean folded tea towel, then place the lid on the pot, making sure it seals tightly. Leave for 5 minutes over medium heat, then turn the heat down to the lowest setting possible; a heat diffuser is best here, especially if cooking on a gas hob.

- Since you can’t really make tahdig with this pilaf (the sugar in the cherry juices burns quickly), reduce the cooking time to about 35–50 minutes. Never remove the lid during this time.

- Have your saffron infusion ready in a bowl (see below). Add some spoonfuls of the rice from the top of the pilaf (without any sour cherries) and mix gently but thoroughly to colour the rice a bright saffron yellow. Serve your albaloo polow on a platter, with the saffron rice scattered on top. You can serve it as a vegetarian main dish, or with chicken or meatballs. At feasts and weddings, slivers of almonds and pistachios are sometimes added to the saffron rice.

For the saffron infusion

- Grind the saffron strands with the sugar in a small mortar. If you don’t have a small mortar, you can put the saffron and sugar on a piece of baking paper, fold all the sides so the powder won’t escape, then grind with a jam jar or rolling pin until you have a very fine powder.

- Boil the kettle, then let it sit for a few minutes. Tip the powder very gently into a small glass teacup, then gently pour 3 tablespoons of the hot water over it. (Never use boiling water, or you’ll ‘kill’ the saffron.) Cover the cup with a lid or saucer and let the mixture ‘brew’ for at least 10 minutes without removing the lid, to release the colour and aroma of the saffron. After this time your saffron infusion is ready to use.

- If you make a larger batch, store the leftovers in a clean sealed jar in the fridge for 4–5 days. You can also make a refreshing drink called a sharbat with any leftover saffron infusion, or add it to your regular cup of tea.

- At least 2-3 hours before you want to serve the dish, gently rinse the rice with cold water, discarding the water. Do this at least three times. The water will always remain a bit cloudy, but rinsing removes the excess starch from the rice, which will make the rice fluffy once cooked, with each grain separated.

- Add the rice to a large bowl, with enough water to cover the rice by at least 5cm (2 inches). Add the salt and fold gently, possibly with your hand. Taste the water: it should be as salty as the sea. Don't worry if the water seems too salty - the rice absorbs the salt it needs, and any excess salt can be rinsed away after the first cooking (the parboiling stage).

- Soak the rice for 2–3 hours, or at least 30 minutes. You can even soak the rice overnight.

- Meanwhile, if you’re using frozen or fresh cherries, let them macerate with the sugar for at least 30 minutes. If using dried cherries, soak them in 1 cup (250 ml) hot water until rehydrated.

- Put the cherries in a saucepan, either with the released juices if using fresh or frozen ones, or with the sugar to taste if using dried cherries. (This is a sweet and savoury dish, so some sugar is needed.) Cook with a lid on for 8–15 minutes, until the cherries are soft, but nowhere near falling apart. Remove them from the syrup.

- Keep about ½ cup (125 ml) of the juices for the rice, and store the remaining syrup to make sharbat.

- Now parboil the rice. Bring a large pot of water to the boil. Add the vegetable oil. Discard most of the soaking water from the rice, without draining it completely, then gently add the rice and what's left of the soaking water to the boiling water. Do not stir the rice too much, or you'll break the grains. If needed, put the lid on to bring the water back up to the boil as quickly as possible. We want to partially cook the rice at this point; meaning the grains will swell, and the outer part of the grain should be soft, but a bit of a bite should remain in the centre (similar to very al dente, if we were talking about pasta). The parboiling time varies depending on the quality of the rice, and even the humidity of the region in which you live. This amount of rice would normally take 5-10 minutes to cook.

- Place a fine-meshed colander in your kitchen sink, then very gently and carefully drain the rice into the colander. Taste the rice. If it's too salty (it shouldn't be), run cold water over the rice for several minutes. Otherwise, run the cold tap water for only about 30 seconds, just to stop the cooking process.

- Melt the ghee with ½ cup (125 ml) water in a heavy-based nonstick saucepan over medium–high heat. With the pot still on the heat, gently scatter in a layer of rice with a slotted spoon, then add a layer of sour cherries. Repeat this layering (never pushing down on the rice), to create a little mountain of rice and sour cherries. Now, using the other end of the slotted spoon, dig some holes in the mound of rice and sour cherries to let the steam rise from the bottom to the top.

- In a small saucepan, heat the reserved cherry syrup with the butter, then drizzle it all over the mound of rice. Wrap the lid in a clean folded tea towel, then place the lid on the pot, making sure it seals tightly. Leave for 5 minutes over medium heat, then turn the heat down to the lowest setting possible; a heat diffuser is best here, especially if cooking on a gas hob.

- Since you can’t really make tahdig with this pilaf (the sugar in the cherry juices burns quickly), reduce the cooking time to about 35–50 minutes. Never remove the lid during this time.

- Have your saffron infusion ready in a bowl (see below). Add some spoonfuls of the rice from the top of the pilaf (without any sour cherries) and mix gently but thoroughly to colour the rice a bright saffron yellow. Serve your albaloo polow on a platter, with the saffron rice scattered on top. You can serve it as a vegetarian main dish, or with chicken or meatballs. At feasts and weddings, slivers of almonds and pistachios are sometimes added to the saffron rice.

For the saffron infusion

- Grind the saffron strands with the sugar in a small mortar. If you don’t have a small mortar, you can put the saffron and sugar on a piece of baking paper, fold all the sides so the powder won’t escape, then grind with a jam jar or rolling pin until you have a very fine powder.

- Boil the kettle, then let it sit for a few minutes. Tip the powder very gently into a small glass teacup, then gently pour 3 tablespoons of the hot water over it. (Never use boiling water, or you’ll ‘kill’ the saffron.) Cover the cup with a lid or saucer and let the mixture ‘brew’ for at least 10 minutes without removing the lid, to release the colour and aroma of the saffron. After this time your saffron infusion is ready to use.

- If you make a larger batch, store the leftovers in a clean sealed jar in the fridge for 4–5 days. You can also make a refreshing drink called a sharbat with any leftover saffron infusion, or add it to your regular cup of tea.

Additional Information

NOTE:

Instead of fresh or frozen sour cherries, you can also use tinned ones, which are already half-cooked. Taste them and check the ingredients list. If they're not sweet, heat the sour cherries in a saucepan with the juices from the tin, adding sugar to your taste; you may not even need to add any sugar. As soon as the sugar has dissolved, turn off the heat, so as not to overcook the cherries. Remove the cherries, reserve about ½ cup (125ml) of the syrup for the rice, and store the remaining juices to make sharbat.

NOTE:

Instead of fresh or frozen sour cherries, you can also use tinned ones, which are already half-cooked. Taste them and check the ingredients list. If they're not sweet, heat the sour cherries in a saucepan with the juices from the tin, adding sugar to your taste; you may not even need to add any sugar. As soon as the sugar has dissolved, turn off the heat, so as not to overcook the cherries. Remove the cherries, reserve about ½ cup (125ml) of the syrup for the rice, and store the remaining juices to make sharbat.

Tell us what you think

Thank you {% member.data['first-name'] %}.

Explore more recipesYour comment has been submitted.